The “Sistine Chapel of Evolution” Is in New Haven, Connecticut

Charles Darwin never visited the Yale museum, but you can, and see for yourself the specimens that he praised as the best evidence for his theory

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/69/a1/69a10c2f-b7d6-41cc-a7de-0ec12adfc600/apr2016_j02_peabodyyale.jpg)

When visitors go to the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, they are not exactly wrong to think that dinosaurs are the stars of the show. This is, after all, the museum that discovered Stegosaurus, Brontosaurus, Apatosaurus, Allosaurus, Triceratops, Diplodocus and Atlantosaurus, among others.

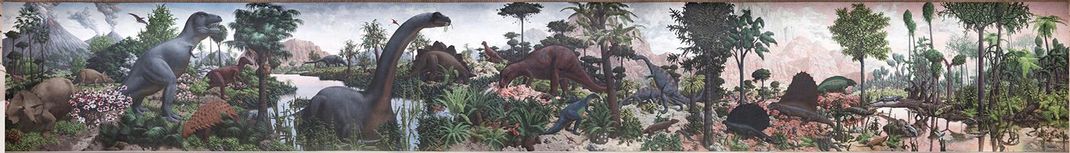

There’s even a 7,350-pound bronze Torosaurus on the sidewalk in front of this red brick Gothic Revival building on the outskirts of downtown New Haven. It was the Peabody that led the great age of paleontological discovery in the 19th century. It also went on to launch the modern dinosaur renaissance in the late 1960s, setting off a global wave of dinomania and incidentally inspiring the Jurassic Park franchise. And Peabody researchers continue to make groundbreaking discoveries. In 2010, they determined, for the first time, the exact coloration of an entire dinosaur, feather by feather. Anchiornis huxleyi is unfortunately still in China, where it was discovered: It looked like a Las Vegas showgirl crossed with a spangled Hamburg chicken. Plus, the Peabody houses one of the most revered images in all of paleontology: The Age of Reptiles, by Rudolph Zallinger, is a 110-foot-long mural depicting dinosaurs and other life-forms in a 362-million-year panorama of Earth’s history, moving one writer to call the museum “a Sistine Chapel of evolution.”

So why on earth go to the Peabody for any reason other than dinosaurs? One answer: for the fossil mammal and bird discoveries that most visitors miss, but which Charles Darwin himself considered the best evidence for the theory of evolution in his lifetime.

These discoveries were largely the work of a brilliant and intensely competitive Yale paleontologist named Othniel Charles Marsh. Though raised in a poor upstate New York farming family, Marsh was a nephew of George Peabody, a merchant banker and promoter of all things American in mid-19th-century London. Peabody built a vast fortune from scratch and then gave much of it away in his lifetime, with an emphasis on the formal education he lacked. The Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, founded at his nephew’s urging in 1866 and now celebrating its 150th anniversary, was one result. Peabody’s wealth also enabled Marsh to lead a series of four pioneering Yale expeditions in the early 1870s, traveling via the new transcontinental railroad and on horseback to explore the American West.

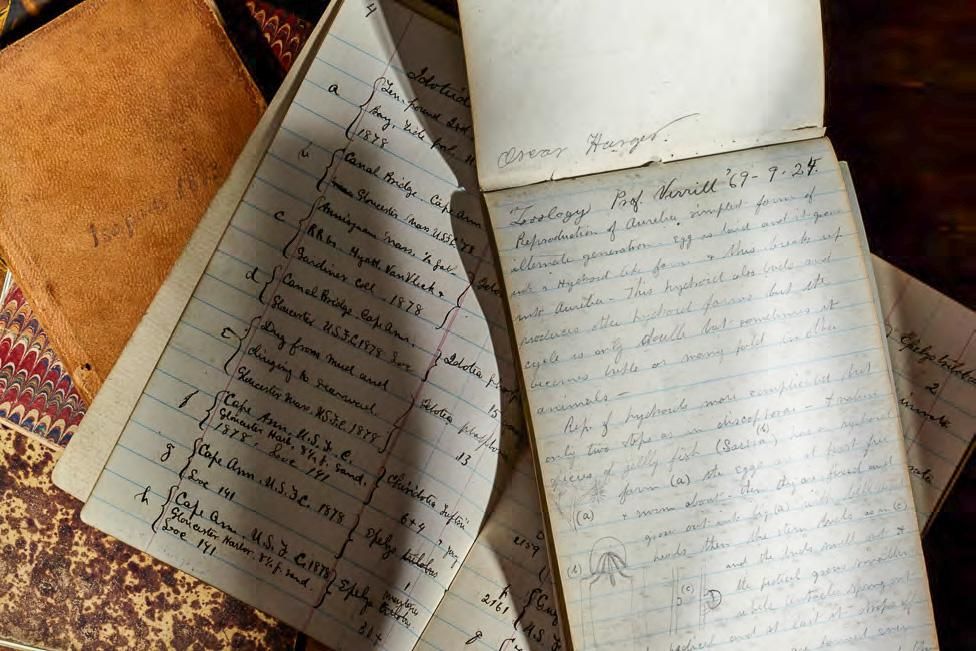

Marsh focused at first not on dinosaurs, then little known, but on a creature of ardent popular and scientific interest: the horse. In January 1870, Thomas Henry Huxley, a British paleontologist nicknamed “Darwin’s Bulldog” for his fierce advocacy of evolutionary theory, used fossils to trace the horse back 60 million years to its supposed origin in Europe. But Marsh and his Yale crews were accumulating a rich fossil record proving, he thought, that the horse had evolved in North America. Huxley was so intrigued that he visited Yale in 1876, intent on seeing the evidence for himself. The two men spent much of an August week at “hard labor” reviewing fossils.

It was a revelation: Huxley would ask to see a specimen illustrating some point about horse evolution, and as Huxley’s son and biographer Leonard later recounted, “Professor Marsh would simply turn to his assistant and bid him fetch box number so and so,” until Huxley finally exclaimed, “I believe you are a magician; whatever I want, you just conjure it up.”

Huxley became a ready convert to Marsh’s argument that horses evolved in North America, and at his request, Marsh cobbled together a celebrated—though not particularly striking—illustration. You can see it now in a display case just past the dinosaurs, in the Peabody’s Hall of Mammals. It’s a lineup of leg bones and molars of different North American species. They show the horse increasing in size and evolving over 50 million years, from Orohippus, with four toes on its front legs, on up to the modern horse with a single hoof—an evolutionary development that allows it to gallop even across hard, flat prairies and deserts.

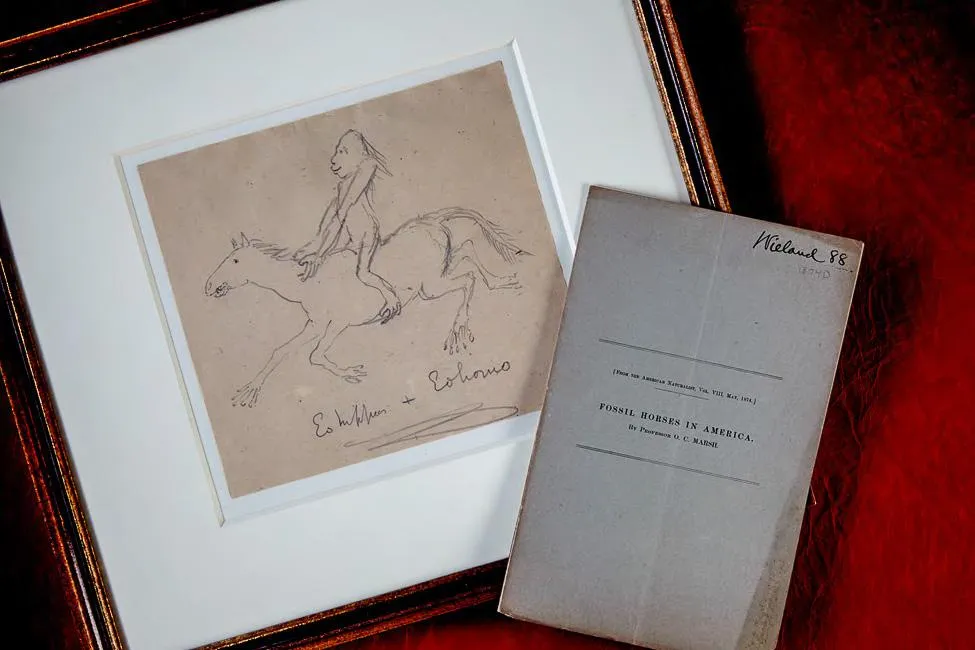

Huxley presented this diagram and outlined the North American story at a lecture that September in New York. He thought Marsh had already discovered enough about the horse “to demonstrate the truth of the evolution hypothesis,” a truth, as the New York Times put it, “which could not be shaken by the raising of side issues.” Huxley also predicted that a more primitive horse would eventually turn up with a fifth toe. He and Marsh had discussed this theoretical “dawn horse,” dubbed Eohippus, and one evening in New Haven, Huxley had sketched a fanciful five-toed horse. Then he’d penciled in an equally fanciful hominid, riding bareback. With a swirling flourish, Marsh had added the caption “Eohippus & Eohomo,” as if horse and cowboy were ambling together out of the sunrise of some ancient American West. Writing a few days after his visit about what he had seen at the Peabody, Huxley remarked, “There is no collection of fossil vertebrates in existence, which can be compared to it.”

What caught the attention of Darwin himself, though, wasn’t so much the horses as a pair of late Cretaceous birds. In the early 1870s, Marsh managed to obtain two spectacular fossil birds—Hesperornis and Ichthyornis— from 80 million-year-old deposits in the Smoky Hills region of north-central Kansas. These specimens had heads, unlike the only specimen of the ancient bird Archaeopteryx then known, and these heads had distinctly reptilian teeth for catching hold of fish underwater.

The discovery, Marsh announced triumphantly, “does much to break down the old distinction between Birds and Reptiles.” In a monograph on the toothed birds of North America, he predicted correctly that Archaeopteryx would also turn out to have had teeth. In 1880, a correspondent was moved to write Marsh, “Your work on these old birds, and on the many fossil animals of North America, has afforded the best support to the theory of Evolution, which has appeared within the last twenty years”—that is, since the publication of On the Origin of Species. The letter was signed, “With cordial thanks, believe me, Yours very sincerely, Charles Darwin.”

Hesperornis and Ichthyornis now occupy a little-noticed display case at the side of the Great Hall of Dinosaurs, overshadowed by the 70-foot-long Brontosaurus hulking nearby and the huge mural overhead. But they are worth a look for one added reason. Marsh eventually published his monograph about the toothed birds through the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). Much later, in the 1890s, a congressman held up a copy of this book as an instance of taxpayer spending on “atheistic rubbish.” His incredulously repeated phrase—“birds with teeth, birds with teeth!”—helped drive a Congressional attack on the USGS, which was then arguing that scientific mapping of the water supply should shape the settlement of the West. Congress soon slashed USGS funding and overrode its warning that pell-mell settlement would yield “a heritage of conflict and litigation over water rights.” People fighting over water in the drought-stricken American West are still feeling the bite of those “birds with teeth.”

**********

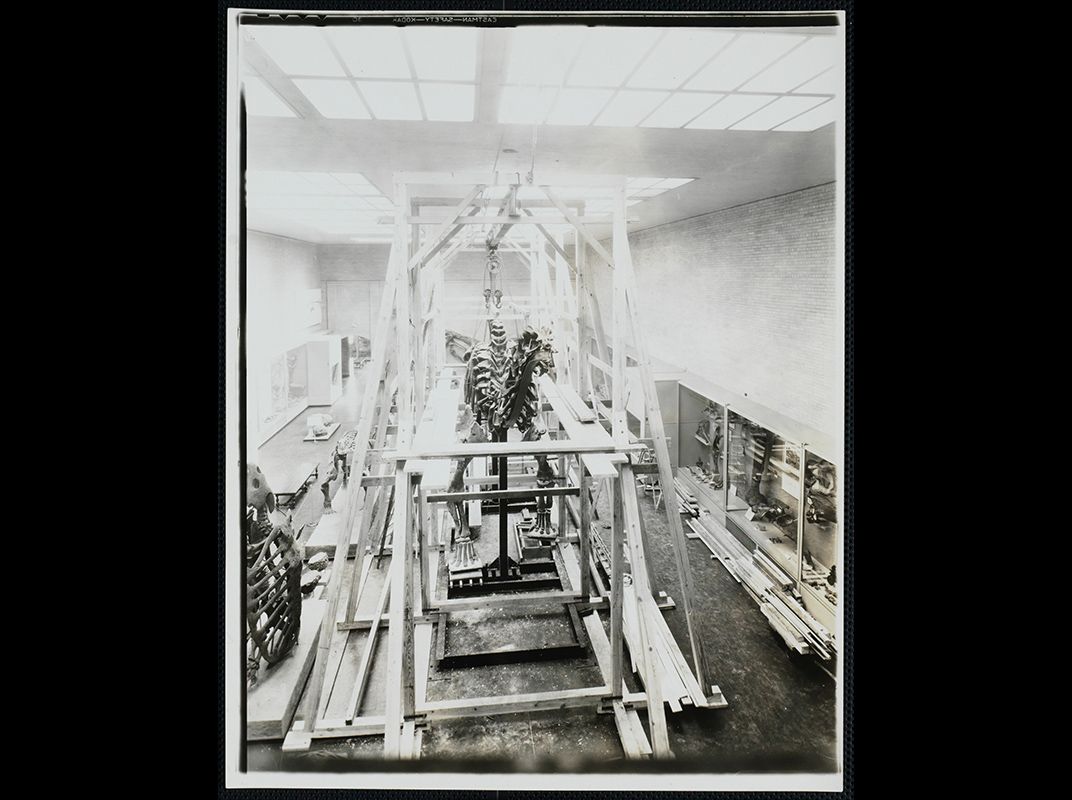

I took a seat on a wooden bench, alone except for a guard, in a room with a dozen or so gigantic dinosaurs on display. Brontosaurus dominates the scene, and it’s easy enough to see why Marsh gave it a name that means “thunder lizard.” The discovery of such enormous dinosaurs began one day in March 1877 when two scientifically minded friends, on a hike above Morrison, Colorado, suddenly found themselves gawking in silence at an enormous fossil vertebra embedded in stone. It was “so monstrous,” one of them wrote in his journal, “so utterly beyond anything I had ever read or conceived possible that I could hardly believe my eyes.”

Marsh had by then withdrawn from fieldwork, instead using his inherited wealth to deploy hired collectors. He was also deeply engaged in a bitter rivalry, now remembered as “the Bone Wars,” with Edward Drinker Cope at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. Marsh managed to edge out Cope for that huge new specimen, naming it Titanosaurus (later Atlantosaurus).

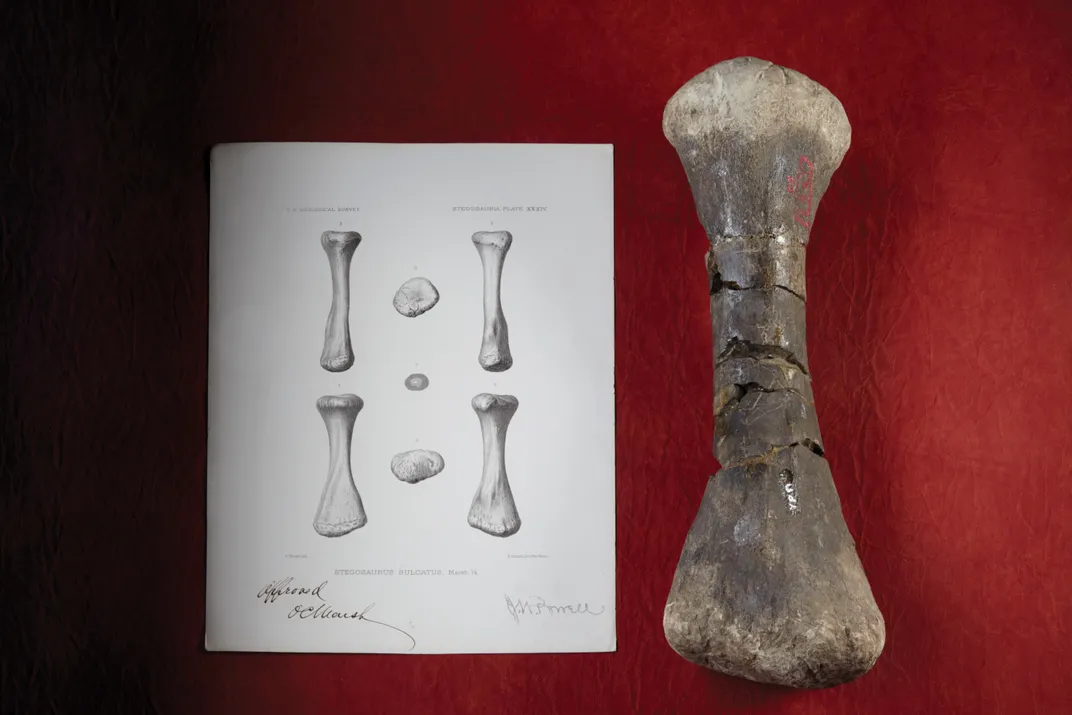

That same year, Marsh’s collectors also found and shipped him the meat-eating Jurassic monster Allosaurus and the plant-eaters Apatosaurus and Stegosaurus. Visitors to the museum today are liable to run their eyes over the massive bulk of Stegosaurus—which weighed five tons, when alive—and notice that its skull seems far too small for an adequate brain. Marsh thought so, too, and conjectured that Stegosaurus must have had a second brain in a large hollow area of its lower vertebrae. His Stegosaurus was long believed to be the inspiration for a celebrated bit of light verse in The Chicago Tribune in 1903, which included these lines:

The creature had two sets of brains—

One in his head (the usual place),

The other at his spinal base.

Thus he could reason a priori

As well as a posteriori.

Although numerous popular books still associate this poem with the Stegosaurus, that connection turns out to be false. In reality, a former student of Marsh’s merely borrowed his two-brain idea and slapped it onto an entirely different dinosaur, Brachiosaurus, at the Field Museum in Chicago. It was the Brachiosaurus that inspired this verse. But let’s at least credit Stegosaurus with an assist. Credit it, too, with only a single brain, described by one modern paleontologist, as roughly “the size and shape of a bent hotdog.”

Nine of Marsh’s dinosaurs turn up in the mural overhead, but only three of Cope’s. (Old rivalries die hard.) Artist Rudolph Zallinger was a 23-year-old at the start in 1942, and later admitted that he did not know “the front end from the rear end of a dinosaur.” He spent four years on the project, and one art historian called the resulting Garden of Eden for dinosaurs the most important mural since the 15th century. In 1953, Life magazine published a fold-out reprint of the original study of the mural, with a detail of Brontosaurus and Stegosaurus on the cover. The mural thus inspired a generation of future paleontologists. It also caught the attention of a moviemaker in Tokyo, who borrowed heavily from Zallinger’s dinosaurs to put together a new monster—Godzilla.

Zallinger’s mural incorporated the then-current dogma, from O.C. Marsh and others, that dinosaurs were plodding tail-draggers. But in 1964, John Ostrom, a paleontologist at the museum, made a discovery that shattered this stereotype. He and an assistant were out for a walk in Bridger, Montana, at the end of that year’s field season, when they spotted what looked like a hand with an outsized claw eroding out of a rocky slope. It was in fact a foot, and that sharp, sickle-shaped claw projecting almost five inches from the innermost toe eventually gave the species its name, Deinonychus, or “terrible claw.”

Studying his find over the next few years, Ostrom began to think that instead of being slow and stupid, Deinonychus “must have been a fleet-footed, highly predaceous, extremely agile and very active animal, sensitive to many stimuli and quick in its responses.” He took this idea an audacious leap forward before the North American Paleontological Convention in 1969. Evidence suggested, he declared, that many dinosaurs “were characterized by mammalian or avian levels of metabolism.” This idea elicited “shrieks of horror” from traditionalists in the audience, according to the paleontologist Robert Bakker, who had been Ostrom’s undergraduate student at Yale and went on to popularize this new view of dinosaurs. It was the beginning of the modern dinosaur renaissance.

The following year, Ostrom began to compare the many similarities between Deinonychus and the ancient bird Archaeopteryx. From that insight, he went on in a series of groundbreaking papers to establish that the bipedal theropod dinosaurs, including Deinonychus, were in fact the ancestors of modern birds. This idea is now so commonplace that researchers debate why birds were the only dinosaurs to survive the mass extinction of 66 million years ago.

The novelist Michael Crichton later spent time interviewing Ostrom in person and by phone, paying particular attention to the capabilities of Deinonychus. He later told Ostrom apologetically that his book Jurassic Park would instead feature Velociraptor, a Deinonychus relative, because the name sounded “more dramatic.” Visitors to the Peabody Museum can, however, still see the original Deinonychus model with its arms and legs flung back and out, elbows bent, claws flared. During a recent visit, a former graduate student of Ostrom’s pointed out an intriguing resemblance: If you take those outstretched arms and swing them back just a little farther (with a few small evolutionary adaptations), that hand-snatching gesture becomes the wingbeat of birds.

The museum is currently raising funds to undertake a dramatic updating of both the Great Hall of Dinosaurs and the Hall of Mammals. (Brontosaurus will no longer drag its tail and Stegosaurus will do combat with Allosaurus.) But it’s worth going now because the outdated displays and the dinosaur reconstructions are somehow evocative of another era in paleontology.

When you go, take a look at another fossil most visitors skip past: It’s a Uintathere, a “beast of the Uinta Mountains.” It lived roughly 45 million years ago on the present-day Utah-Wyoming border, and it looked like a rhinoceros, but with long, saber-like upper canines, and three sets of knobs, like the ones on the head of a giraffe, running from its nose to the top of its oddly flattened head.

This Uintathere was one of the first reconstructions O.C. Marsh approved for display in the museum. Marsh generally liked to reconstruct fossil animals only on paper, with the actual bones safely stored away for study. So he nervously ordered his preparator to construct a Uintathere entirely out of papier-mâché. Because of the scale of the Uintathere, this required paper with a high fiber content. According to backroom lore, the perfect raw material arrived at the museum one day after Marsh prevailed on friends in high places to provide U.S. currency otherwise destined for destruction.

The sign on the display does not say so. But you can pass on the tale to your companions: What you are looking at may be quite literally the first “million-dollar fossil.”

Related Reads

House of Lost Worlds: Dinosaurs, Dynasties, and the Story of Life on Earth

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/richard-conniff-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/richard-conniff-240.jpg)